Published: October 5, 2025, 07:39 PM

A preventable yet deadly crisis grips rural Bangladesh as snakebite envenoming kills over 7,500 people each year. Outdated treatment, reliance on foreign antivenoms, and harmful traditional practices keep this solvable emergency claiming lives in silence.

Image: AI Generated/TNC

In Bangladesh’s countryside, where green paddy fields seem to go on endlessly and farmers toil barefoot from dawn till dusk, a deadly and silent threat takes lives every single day—without headlines or politician interest. Snakebite envenoming, though preventable and treatable in whole, ranks among the country’s deadliest and most overlooked public health emergency.

Approximately 400,000 snakebites are estimated every year, killing more than 7,500 individuals—among the highest snakebite mortality rates globally. In addition to the death tolls, more than 10% of survivors are permanently crippled, losing their livelihoods and means of feeding their loved ones. The horror deepens because around 95% of these bites happen in rural areas, predominantly among men engaged in agricultural work, fishing, and other outdoor occupations.

Why does such a solvable problem continue in the twenty-first century? The reasons lie in outdated treatment methods, inadequate health infrastructure, reliance on unsuitable imported remedies, and deeply ingrained community practices that delay or even block lifesaving medical intervention.

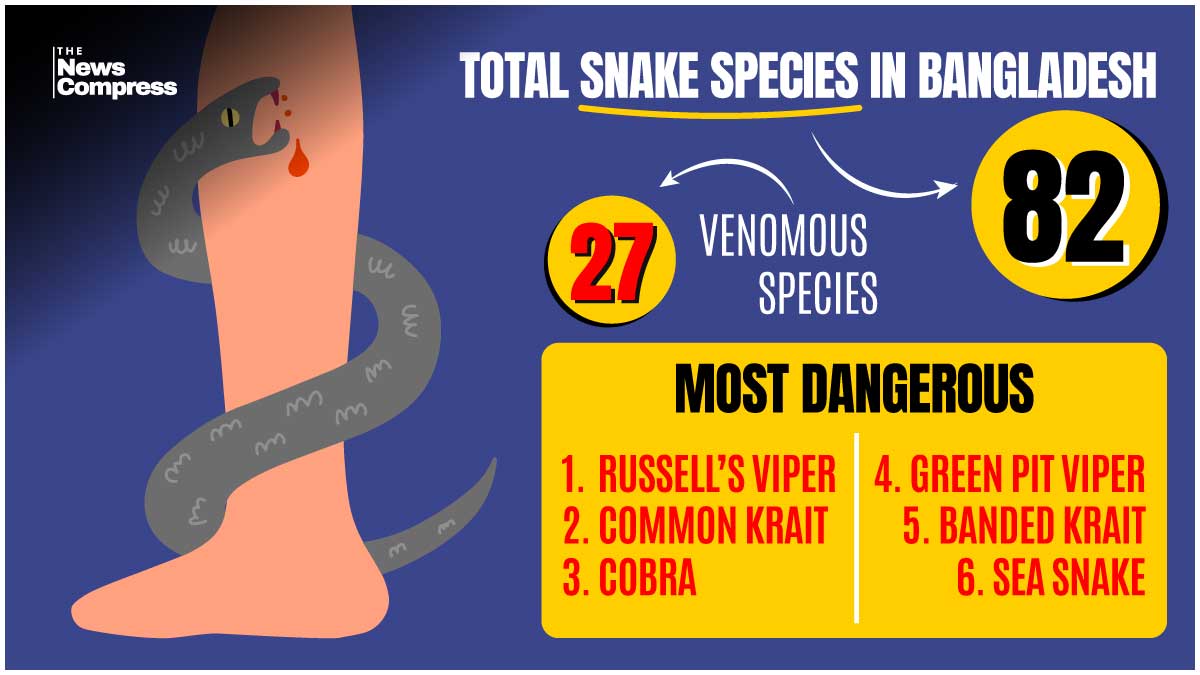

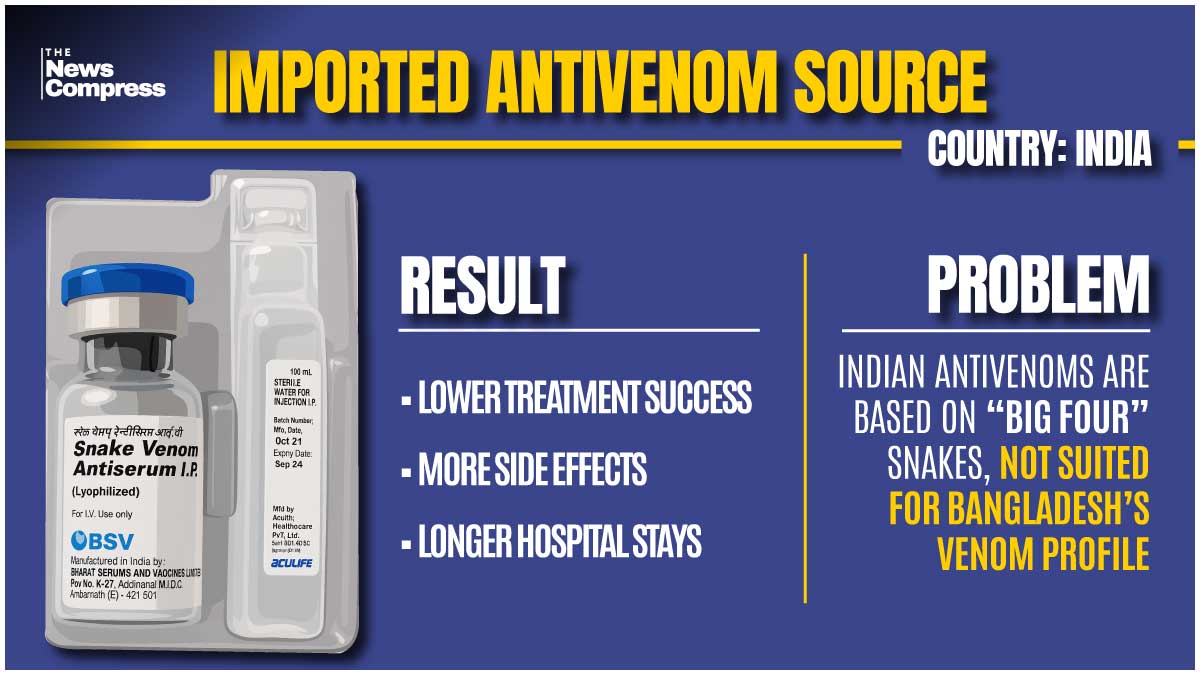

Bangladesh has about 82 snake species, of which 27 are venomous. Six of these pose the highest threat to humans, including the feared Russell’s viper. And the country still relies completely on imported anti-venoms—principally from India. These are polyvalent preparations tested on India’s “Big Four” snakes, and they are not an exact fit with the venom profiles of Bangladesh’s snakes. The result of this incompatibility tends to be lower success of treatment from the beginning, more likely to cause mortality, prolonged stay in hospital, and common overdose effects. In contrast, Sri Lanka and some Indian states have regionally developed their antivenoms to suit the regional fauna, and survival rates have improved substantially and unwanted effects decreased accordingly.

Scientific findings from South Asia confirm an old intuition of Bangladeshi health practitioners—antivenoms composed of a narrow portfolio of snakes of a region are unable to neutralize another region’s diverse venom. National health authorities and the World Health Organization have initiated recommending the production of Bangladesh-specific antivenoms, including the country’s most lethal species’ venom repertoire. Taken up, such production could substantially improve successful therapy, reduce unwanted dosing, and reduce adverse effects. Public health advantages would be fewer deaths, less disability, and more people returning to work in fields, rivers, and other rural activities.

However, better antivenoms alone will not save lives if victims cannot reach hospitals in time. In villages nationwide, dangerous first-aid methods are still common. Tourniquets are applied in over three-quarters of cases, despite evidence that they damage tissue and worsen outcomes. Many victims seek out traditional healers first—sometimes traveling for hours—while venom spreads rapidly through their bodies. These delays are often fatal. Education programs have shown that this deadly cycle can be broken. When rural communities learn the correct response—immobilize the limb, avoid cutting or sucking the wound, and rush to a hospital equipped with antivenom—hospital visits double, tourniquet use falls sharply, and more victims survive. Initiatives using clinics, schools, folk theatre, radio, and volunteer networks have proven that culturally relevant and persistent messaging can quickly change harmful practices.

Even if patients make it to health facilities, another obstacle lies in store: the preparedness of the health system. Victims first seek assistance at Upazila Health Complexes or rural hospitals, but they are frequently lacking in necessary supplies, trained staff, or explicit guidelines defining proper treatment. Health workers may be unaware of WHO’s latest guidelines, be unsure of proper dosing, or unfamiliar with the regional form of venomous snakes. Supplementing these base facilities is necessary. Training of rural health providers in modern snakebite therapy, assuring a regular free supply of antivenom at the district and Upazila levels, and conceiving rapid referral mechanisms for extreme cases have the potential to cut deaths drastically. WHO-supported efforts in Bangladesh have already trained hundreds of health providers, and they have shown genuine reductions around peak-risk periods such as flood aftermaths.

Those critical initial hours of a snakebite may spell life or death. The message has to be short, concise, and universal: remain calm, keep the affected limb immobile and below the level of the heart, take off constricting clothes or accessories, eschew dangerous traditional medicine, and get to the hospital quickly—preferably in under four hours. Wrong beliefs regarding cutting the bite, draining off the venom, or applying a tourniquet have to be dispensed with through sustained public health education.

Beating the snakebite pandemic is an issue of medicine, but of justice and fairness as well. Rural laborers, fishers, and farmers, who are the economic lifeblood of Bangladesh, are the face of the forgotten disease, but their concern has been largely overlooked in mainstream urban debates about policy. Fighting snakebite envenoming requires swift, coordinated action: develop region-appropriate antivenoms, conduct sustained national education campaigns to replace deadly traditions, enhance health facilities from village clinics upward, and make sure vulnerable groups, such as nomads like the Bede, are brought into preventive and curative programs fully.

This emergency is fully treatable. Other countries with fewer means have achieved remarkable success through the union of scientific advancement and community action. Bangladesh can and must follow suit. Delay every day results in additional preventable fatalities. The invisible pandemic of snakebite envenoming requires a vocal, unanimous, and tenacious response. With focused investments, evidence-informed policies, and collective will, Bangladesh may save lives, safeguard its rural populations, and set an exemplary course against one of the globe’s most ancient and deadly natural dangers.